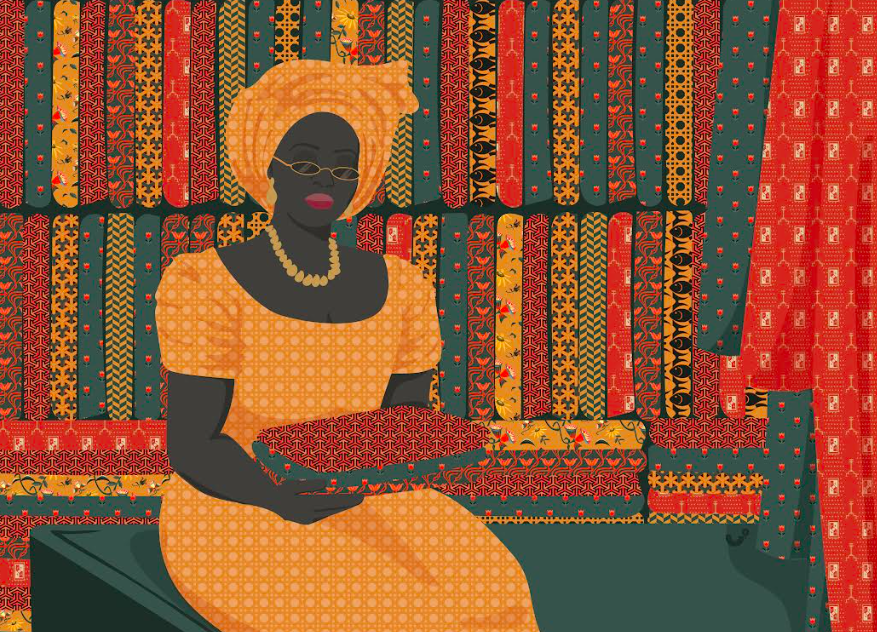

How African is Ankara Print?

Growing up in Nigeria, I knew early on that my Grandmother’s ‘Hollandais’ / ‘African Wax’ fabrics were precious. She took good care of them, and liberated them from their dedicated travel box only on special occasions and for Church. That box contained a myriad of high quality prints, falling across all spectrums of the rainbow. Examining each print was, and is, an experience because so much detail and colour tickle the senses!

The African Wax, or Ankara, has been a staple traditional cloth in most West African homes. Women keep them not just to wear and look/feel good, but also as a store of value; the beautiful high quality prints are valuable and easy to push if you need cash now.

These days, Ankara is still the go-to fabric to create made-to-wear dresses for special occasions, or even something to just laze around at home in. But it has also become synonymous with the young, enlightened African in Diaspora who wants to wear something that immediately showcases their West African culture, and their love for it. And at home in Africa, it is omnipresent.

But Ankara as a definitive display of West African culture has been faced with an unending controversy - is it really African?

Why do people say Ankara isn’t African?

For one, the process of creating the Ankara print has no history in ancient West Africa. The print has its roots in the Indonesian batik technique where wax is melted and used to pattern a blank cloth. Batik is a handmade technique that has shown up across different ancient civilisations in Asia.

But the Dutch, as they colonised Indonesia, saw an opportunity to capitalise on the rich batik market in the region. And so they explored mechanised methods of production as industrial nations tend to do. The new and imitated print was, of course, lower quality to the Indonesians and they didn’t relate to it. But these traders, who typically stopped at different West African ports, realised they had a market in that region. Particularly in Ghana at the time. Even the name, Ankara, is a bastardised version (by African traders) of the name of Ghana’s capital, Accra.

It is because of this history - Dutch traders introducing the West African coast to the print, that it’s still known as Dutch Wax. The questions are therefore relevant - how can something steeped in Dutch and colonial history be a representation of Africa?

Secondly, to this day, most of the Ankara fabric is still produced in the Netherlands. Particularly Vlisco, which has been trading in Ankara print since the 1800s. Since the beginning. Another sizeable amount, though of lesser quality, is produced in China. A much smaller percentage is manufactured by five local factories, three of which are owned by Vlisco. An infinitesimal percentage is produced by disparate hyper-small local factories across West Africa - primarily Ghana, Cameroon, and Nigeria.

This begs another question - how can something manufactured mostly (some say up to 90%) outside of Africa be a representation of Africa?

Why do many still think of Ankara as African?

Regardless of the extraordinary influence of the Dutch on the Ankara fabric, it was made for Africans, shaped with our preferences in mind. And till now, sold literally exclusively to West Africans. This adaptation is so complete that the Ankara we’ve always known bares zero resemblance to the batiks of its origins.

What’s more, each print speaks to the colourfulness, loudness and liveliness that most West Africans are culturally known for.

The narrative has also been well and truly captured such that many of the most popular and classic prints (some going on 150 years strong) have names and African proverbs associated with them. There are lasting print designs such as one celebrating the renown Ghanian music, Highlife, and another describing just how flighty money is by depicting birds fleeting to and away.

Overall, Ankara is African because Africans have chosen it to be.

How can the narrative become fully African?

Regrettably, the African wax print will still always also be known as ‘Dutch wax’ as long as so much of it is produced by the Dutch. The controversy of Ankara being truly African will linger until West Africa solves a major problem that affects every single part of its economy - the problem of being a producer rather than just a consumer. Micro factories will forever remain small and be dwarfed by Vlisco and China as long as the energy deficit that plagues all manufacturing plants in West Africa persists.

We remain hopeful.

For more about this debate, view this interesting and short video below.

Words by Adiya, and image by Urechi Oguguo for Muse Origins.